The power of

community in

inflammatory bowel

disease

Coming together to reduce

physical and psychosocial impacts

Contributors: Aline Charabaty, MD, AGAF, FACG, Associate Professor of Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Medical Director of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and Clinical Director of the IBD Center, Johns Hopkins-Sibley Memorial Hospital; Brooke Abbott Abron, Founder, IBDMoms, IBD Social Circle Advocate; Tina Aswani-Omprakash, MPH, CEO, South Asian IBD Alliance, IBD Social Circle Advocate; Laurie Keefer, PhD, Clinical Health Psychologist and Professor of Medicine, Psychiatry and Biomedical Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Amy Stewart, FNP-C, Nurse Practitioner, Capital Digestive Care

Executive summary and approach

For the millions of people in the United States (US) living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),1 its impact goes well beyond physical symptoms. IBD is an immune-mediated disease where the immune system responds to perceived threats by primarily attacking the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.2 It is often described as an “invisible illness,” as symptoms are not always immediately apparent to others. While someone with IBD may look healthy from the outside, the reality is that they may be experiencing abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, brain fog, mental health challenges, and more.3,4

Given the unpredictable and potentially embarrassing symptoms and physical signs of the disease, such as frequent or urgent bathroom use, perianal fistulae, an ostomy, and/or fatigue, people with IBD may feel the disease limits their ability to venture far from home or socialize comfortably and be fully present at work.5 Up to 84% of adults with IBD feel that there is perceived disease-related stigma against them, which results in social stereotypes making them seem unreliable or antisocial.6

Given the unpredictable and potentially embarrassing symptoms and physical signs of the disease, such as frequent or urgent bathroom use, perianal fistulae, an ostomy, and/or fatigue, people with IBD may feel the disease limits their ability to venture far from

Given the unpredictable and potentially embarrassing symptoms and physical signs of the disease, such as frequent or urgent bathroom use, perianal fistulae, an ostomy, and/or fatigue, people with IBD may feel the disease limits their ability to venture far from home or socialize comfortably and be

home or socialize comfortably and be fully present at work.5 Up to 84% of adults with IBD feel that there is perceived disease-related stigma against them, which results in social stereotypes making them seem unreliable or antisocial.6

fully present at work.5 Up to 84% of adults with IBD feel that there is perceived disease-related stigma against them, which results in social stereotypes making them seem unreliable or antisocial.6

As a result, these individuals may limit their social interactions; face loneliness; and be susceptible to social stigma that may negatively impact quality of life, psychological functioning, and even treatment adherence.5

In addition, people with IBD can experience a delayed diagnosis due to not seeking medical care, a misdiagnosis by their treating doctor, or a combination of both. In one study, patients who ultimately were diagnosed with IBD experienced more GI symptoms than usual compared to the general population in each of the 10 years prior to diagnosis.7 Something that further compounds this challenge is that the somewhat disparate symptoms of IBD experienced by individuals, such as diarrhea and fatigue, may not be recognized by their doctors as connected or signs of the disease, further delaying diagnosis and treatment.5,7 These factors can prolong an individual's social isolation or contribute to a lack of social support.5

After receiving a diagnosis, people with IBD can find navigating the treatment plan process overwhelming. Given the variety of treatment options, like medicines and surgery, or a combination of both, it can be hard for people living with IBD to decide which option is right for them. This can cause treatment-related anxiety, especially when patients may have limited time or access to their healthcare provider (HCP) to ask questions.2,8,9 Despite the broad availability of safe and effective treatments, some people with IBD may have only a partial response to therapy, meaning that symptoms only improve to a certain degree, leading to persistent disease activity and symptoms requiring frequent medical attention.2 Even for those who are considered in a state of remission, where they experience a significant reduction or absence of IBD symptoms to the point where they “feel better,” IBD and ongoing treatments can continue to affect individuals’ quality of life.2

After receiving a diagnosis, people with IBD can find navigating the treatment plan process overwhelming. Given the variety of treatment options, like medicines and surgery, or a combination of both, it can be hard for people living with IBD to decide which option is

After receiving a diagnosis, people with IBD can find navigating the treatment plan process overwhelming. Given the variety of treatment options, like medicines and surgery, or a combination of both, it can be hard for people living with IBD to decide which option is right for them. This can cause treatment-related

After receiving a diagnosis, people with IBD can find navigating the treatment plan process overwhelming. Given the variety of treatment options, like medicines and surgery, or a combination of both, it can be hard for people living with IBD to decide which option is right for them. This can cause treatment-related anxiety, especially when patients may have limited time or access to their healthcare provider (HCP) to ask questions.2,8,9 Despite the broad availability of safe and effective treatments, some people with IBD may have only a partial

right for them. This can cause treatment-related anxiety, especially when patients may have limited time or access to their healthcare provider (HCP) to ask questions.2,8,9

Despite the broad availability of safe and effective treatments, some people with IBD may have only a partial response to therapy, meaning that symptoms only improve to a certain degree, leading to persistent disease activity and symptoms requiring frequent medical attention.2 Even for those who are considered in a state of remission, where they experience a significant reduction or absence of IBD symptoms to the point where they “feel better,” IBD and ongoing treatments can continue to affect individuals’ quality of life.2

anxiety, especially when patients may have limited time or access to their healthcare provider (HCP) to ask questions.2,8,9 Despite the broad availability of safe and effective treatments, some people with IBD may have only a partial response to therapy, meaning that symptoms only improve to a certain degree, leading to persistent disease activity and symptoms requiring frequent medical attention.2 Even for those who are considered in a state of remission, where they experience a significant reduction or absence of IBD symptoms to the point where they “feel better,” IBD and ongoing treatments can continue to affect individuals’ quality of life.2

response to therapy, meaning that symptoms only improve to a certain degree, leading to persistent disease activity and symptoms requiring frequent medical attention.2 Even for those who are considered in a state of remission, where they experience a significant reduction or absence of IBD symptoms to the point where they “feel better,” IBD and ongoing treatments can continue to affect individuals’ quality of life.2

Given the myriad physical and psychosocial challenges these individuals face, the needs of the IBD community extend beyond just finding the right treatment plan. As with other stigmatized chronic diseases (eg, HIV/AIDS, type 2 diabetes, obesity, etc), a sense of community and support from care teams and others living with IBD may provide substantial value.5 It can help these individuals overcome isolation and loneliness, become their own advocates for the care they deserve, and, ultimately, help improve their overall health.

Over the years, the internet has become an essential health resource, with millions of people globally relying on online sources for information and guidance. Online communities, including those on social media platforms, have gained popularity largely because of their accessibility and, often, anonymous nature, helping address some of the physical barriers and privacy concerns people may face when trying to find a community and disease-related information. In fact, on Facebook, over 1.8 billion of the platform’s 2.91 billion users engage with health-related groups monthly, forming over 10 million online health-related support communities.10

In 2014, recognizing the emerging value of online health communities and the lack of support for people with IBD, Johnson & Johnson founded IBD Social Circle—an online patient community built for advocates by advocates. IBD Social Circle was designed to empower and amplify patient, care partner, and HCP voices, and create an inclusive space for community support. Since its inception over a decade ago, this online community has provided people with resources, stories, and, most importantly, opportunities to connect and build supportive relationships among people with shared experiences—ensuring that no one feels alone on their IBD journey.

While those who have benefited from online IBD communities have expressed their value, little quantitative research exists assessing the importance of community in the disease journey of adults with IBD.

Building on its nearly three-decade commitment to advancing care for people living with chronic immune-mediated diseases, Johnson & Johnson commissioned research of adults with IBD living in the US. Johnson & Johnson also conducted in-depth one-on-one interviews with patient advocates, a gastroenterologist with a focus on IBD care, a nurse practitioner who specializes in GI illness, and a mental health expert with a focus on chronic GI illnesses to better understand perspectives on the physical and psychosocial impacts of IBD, best approaches to care, and the role community provides within their health ecosystem.

About the research:

Conducted online in the US by The Harris Poll, on behalf of Johnson & Johnson, among 511 US adults aged 18 and over who have been diagnosed with, and are currently living with or managing, IBD—including IBD, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. If the respondent was living with or managing both IBD and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), their current diagnosis was classified as IBD. The survey was conducted June 26, 2024 to July 9, 2024. Refer to the appendix for the full methodology.

The goal of this research was to discover how physical and psychosocial factors impact patient care, examine the tangible benefits of community, and explore whether community can support people with IBD in all aspects of their disease management.

While the survey* (commissioned by The Harris Poll) and additional research included in this paper provide helpful insights into IBD, more research is needed to confirm and strengthen these findings.

IBD is an immune-mediated disease that involves dysregulation of the immune system. It is an “umbrella” term for a group of conditions characterized by chronic inflammation of the GI tract.2 It is estimated that 6.8 million people around the world are living with IBD, an approximate 85% increase since 1990.11 In the US, the prevalence of IBD is estimated to be between 2.4 and 3.1 million.12

IBD is an immune-mediated disease that involves dysregulation of the immune system. It is an “umbrella” term for a group of conditions characterized by chronic inflammation of the GI tract.2 It is estimated that

IBD is an immune-mediated disease that involves dysregulation of the immune system. It is an “umbrella” term for a group of conditions characterized by chronic inflammation of the GI tract.2 It is estimated that 6.8 million people around the

6.8 million people around the world are living with IBD, an approximate 85% increase since 1990.11 In the US, the prevalence of IBD is estimated to be between 2.4 and 3.1 million.12

world are living with IBD, an approximate 85% increase since 1990.11 In the US, the prevalence of IBD is estimated to be between 2.4 and 3.1 million.12

The two most common forms of IBD are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Crohn’s disease (CD) is a condition that causes inflammation of any part of the GI tract—from the mouth to the anus—but most commonly the large intestine, also known as the colon, and the terminal ileum (the last part of the small intestine).3 This inflammation can affect all layers of the bowel wall, which can lead to complications such as stricture (a narrowing of the bowel) and perforation of the bowel. This can lead to abscesses and fistulae (an abnormal tract between the bowel to another organ or the skin). The inflammation associated with CD typically causes diarrhea, urgency, abdominal pain, and cramps, among other symptoms.3

- Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects only the large intestine, also known as the colon, and the inflammation is limited to the superficial layers of the colon.4 The inflammation associated with UC typically causes blood in the stool, urgency, and cramps, among other symptoms.4

When IBD affects other parts of the body, this is known as an extraintestinal manifestation (EIM). Between 25% and 40% of people with IBD experience EIMs, commonly in the joints, skin, eyes, and liver.12,13 The active and chronic inflammation in the gut can lead to malabsorption and/or loss of nutrients that can contribute to low levels of iron, vitamin B12 deficiency, and anemia.14

When IBD affects other parts of the body, this is known as an extraintestinal manifestation (EIM). Between 25% and 40% of people with IBD experience EIMs, commonly in the joints, skin, eyes, and liver.12,13 The

When IBD affects other parts of the body, this is known as an extraintestinal manifestation (EIM). Between 25% and 40% of people with IBD experience EIMs, commonly in the joints, skin, eyes, and liver.12,13 The active and

active and chronic inflammation in the gut can lead to malabsorption and/or loss of nutrients that can contribute to low levels of iron, vitamin B12 deficiency, and anemia.14

chronic inflammation in the gut can lead to malabsorption and/or loss of nutrients that can contribute to low levels of iron, vitamin B12 deficiency, and anemia.14

While the exact cause of IBD is not fully understood, research suggests that an individual may develop IBD as a result of a combination of genetic factors, a dysregulated gut immune system (e.g., bacterial imbalance in the gut or altered gut immune system response to organisms and other elements in the gut) and environmental factors (e.g., smoking, antibiotics, eating ultra-processed foods).15

There is no single test to diagnose IBD. A diagnosis is made by looking at symptoms, laboratory anomalies, physical exam findings, cross-sectional imaging (CT, MRI, intestinal ultrasound), colonoscopy, and, sometimes, video capsule endoscopy.16,17

While IBD has no cure, remission—which means resolution of the disease symptoms and sometimes, of the gut inflammation—is possible with adequate long-term therapy.2,18 However, even when the gut inflammation is under control or in remission, many people with IBD report that they still experience symptoms and an impaired quality of life compared to the general population,2 and continuous care for the remainder of their lives is needed to remain in remission.

While IBD has no cure, remission—which means resolution of the disease symptoms and sometimes, of the gut inflammation—is possible with adequate long-term therapy.2,18 However, even when the gut inflammation is under

While IBD has no cure, remission—which means resolution of the disease symptoms and sometimes, of the gut inflammation—is possible with adequate long-term therapy.2,18 However, even when the gut inflammation is under control

control or in remission, many people with IBD report that they still experience symptoms and an impaired quality of life compared to the general population,2 and continuous care for the remainder of their lives is needed to remain in remission.

or in remission, many people with IBD report that they still experience symptoms and an impaired quality of life compared to the general population,2 and continuous care for the remainder of their lives is needed to remain in remission.

There can also be lifelong physical, mental, financial, and emotional challenges faced by people with IBD, as well as a different degree of medical trauma, since disease monitoring and treatment often require invasive measures like colonoscopy, and frequent (and sometimes uncomfortable) testing and medical visits.5,8,16 As a result, the physical symptoms and psychosocial burdens contribute to ongoing isolation and stigma19—making community support critical.

What is remission in IBD?

Because IBD is a chronic condition with no cure, the goal of maintenance medical therapy is to control symptoms and inflammation in the gut and prevent flare-ups and the development of disease complications. Remission is the ultimate goal of treatment, although there are different types of remission that gastroenterologists use to measure patient wellness:20-22

- Clinical remission: The patient experiences a reduction or absence of IBD symptoms to the point that they “feel better.”

- Biochemical remission: Blood work and stool tests do not show signs of inflammation in the gut (ie, inflammatory markers, including c-reactive protein, and/or fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin have normalized).

- Endoscopic remission: Minimal or no inflammation is seen in the gut mucosa (the lining of the digestive tract) during a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy.

- Histologic remission: Biopsies of tissue taken during a colonoscopy from the previously inflamed bowel no longer show signs of inflammation under the microscope.

- Radiologic remission: A resolution of signs of active inflammation based on imaging tests like CT or magnetic resonance enterography (MRE).

From a medical standpoint, the ultimate goal of therapy is to achieve a combination of the remission measures above, such as clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic remission—as it may signify the absence of inflammation and symptoms.22 However, there is a lack of consensus on how healthcare teams—and, importantly, people with IBD—define remission, as many of the medical definitions of remission fail to account for the psychosocial impact and challenges of living with IBD.23

Broadly, there are three levels of community: individual connections (partners, family, friends, etc), local (people who share a geographic area and resources), and society (or association with one another). People with IBD

Broadly, there are three levels of community: individual connections (partners, family, friends, etc), local (people who share a geographic area and resources), and society (or association with one another). People with IBD report feeling isolated at all three of these levels of community. According to the survey:

- Most people with IBD said they preferred to stay home because of their IBD (82%) and that they felt isolated as a result of their disease (78%).

report feeling isolated at all three of these levels of community. According to the survey:

- Most people with IBD said they preferred to stay home because of their IBD (82%) and that they felt isolated as a result of their disease (78%).

- They also said that having IBD makes it harder to socially engage with other people (80%).

- More than 2 in 5 people with IBD (43%) said living with and managing their IBD has negatively impacted their social inclusion and sense of community.

- Further, 85% said they felt misunderstood, agreeing that most people do not understand what they are going through and the challenges they face.

The factors that contribute to this isolation are multidimensional and reinforce the need for community support, including in-person connections and online platforms, when living with IBD.

Financial burden and work/school productivity impairment

According to the survey, people with IBD have typically missed five days of work in the past 12 months as a result of their disease,† with 10% missing more than 30 days of work each year—the equivalent of one month. One study also found that when people with IBD are able to attend work, they often must manage challenges like fatigue, chronic abdominal pain, and diarrhea, requiring frequent bathroom use.24 These individuals may be fearful of disclosing their diagnosis and symptoms at their workplace or requesting accommodations to feel more comfortable. A separate study found that up to 70% of people with IBD may experience difficulty focusing at work and completing tasks, and many have shorter workdays due to their disease symptoms.24

Absenteeism, or time missed, among people with IBD is also a significant concern, with one study finding that these individuals miss approximately 16% of their working hours and experience significant functional impairment for almost half of their total working time.24 Additionally, in the survey, 78% of people with IBD shared that their IBD has had a negative effect on their confidence at work and/or school, with younger people with IBD more likely to feel the negative impact compared to their older counterparts.‡

Absenteeism, or time missed, among people with IBD is also a significant concern, with one study finding that these individuals miss approximately 16% of their working hours and experience significant

Absenteeism, or time missed, among people with IBD is also a significant concern, with one study finding that these individuals miss approximately 16% of their working hours and experience significant functional impairment for

Absenteeism, or time missed, among people with IBD is also a significant concern, with one study finding that these individuals miss approximately 16% of their working hours and experience significant functional impairment for almost half of their total working time.24 Additionally, in the survey, 78% of people with IBD shared that their IBD has had a negative effect on their confidence at work and/or school, with younger people with IBD more likely to feel

functional impairment for almost half of their total working time.24 Additionally, in the survey, 78% of people with IBD shared that their IBD has had a negative effect on their confidence at work and/or school, with younger people with IBD more likely to feel the negative impact compared to their older counterparts.‡

almost half of their total working time.24 Additionally, in the survey, 78% of people with IBD shared that their IBD has had a negative effect on their confidence at work and/or school, with younger people with IBD more likely to feel the negative impact compared to their older counterparts.‡

the negative impact compared to their older counterparts.‡

Due to the fluctuating nature of symptoms and unexpected flare-ups, it can be difficult to commit to future work tasks or make career plans, which may ultimately affect someone’s career growth or trajectory.24 In fact, nearly one-third of people with IBD report they have lost their job specifically due to the disease.24

These challenges with job security are compounded by the overall financial burden of managing the disease. A 2024 survey from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation found that more than 40% of people with IBD have made significant financial trade-offs to afford their healthcare, including giving up vacations or major household purchases, increasing credit card debt, and cutting back on essential items such as food, clothing, and basic household items.25

Mental health

Mental health is a significant yet overlooked aspect of IBD care, with the survey revealing that more than half (52%) of people with IBD consider the impact of IBD on their mental well-being as negative. Other research has shown that some of the most common psychological conditions in people with IBD are depression and anxiety—with as many as 40% and up to 30%, respectively, experiencing these comorbidities—and some experiencing one or both, even in remission.26,27

Mental health is a significant yet overlooked aspect of IBD care, with the survey revealing that more than half (52%) of people with IBD consider the impact of IBD on their mental well-being as negative. Other research has shown that some of the most common

Mental health is a significant yet overlooked aspect of IBD care, with the survey revealing that more than half (52%) of people with IBD consider the impact of IBD on their mental well-being as negative. Other research has shown that some of the most common psychological conditions in people with IBD

psychological conditions in people with IBD are depression and anxiety—with as many as 40% and up to 30%, respectively, experiencing these comorbidities—and some experiencing one or both, even in remission.26,27

are depression and anxiety—with as many as 40% and up to 30%, respectively, experiencing these comorbidities—and some experiencing one or both, even in remission.26,27

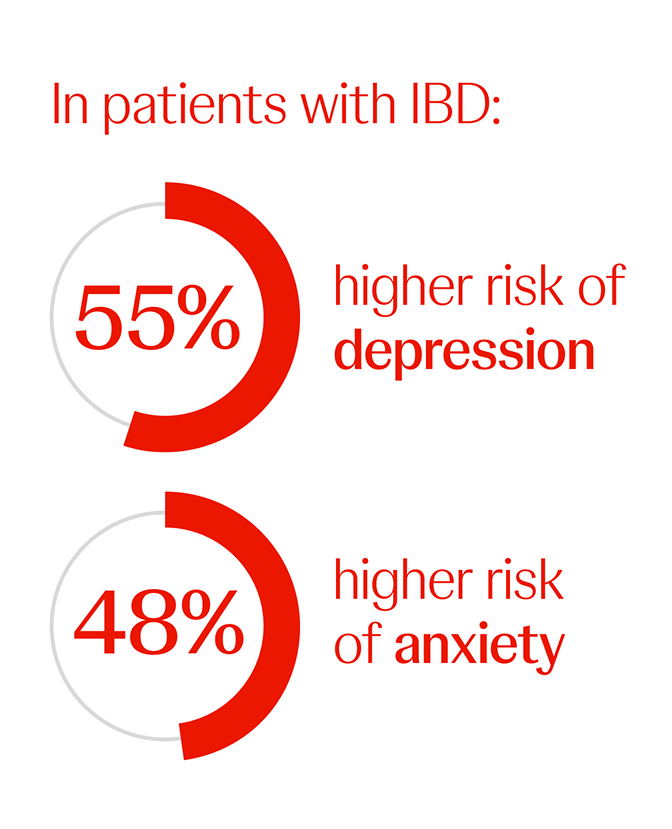

Another study reported that the risk of depression and anxiety in patients with IBD is increased by 55% and 48%, respectively, compared to the general population.28 Research also suggests that the need to follow a long-term disease-friendly dietary regimen can cause or exacerbate anxiety around food.8

In addition to the mental burden of adjusting to life with IBD, many individuals—approximately one-third, according to one study—also encounter medical post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms associated with their disease.29 The psychosocial effects of IBD can impact quality of life and social functioning and are associated with poorer patient outcomes.8,28 Those with higher PTS symptoms are less likely to be in remission and may utilize more outpatient GI services or require hospitalization.28 Psychosocial distress, which includes depression or anxiety, may also correlate to poor medication adherence for those living with IBD.30

Family, friends, and care partners

IBD can impact relationships with care partners, family members, parents, children, and friends. The disease often leads to strain due to its unpredictable nature, the need for frequent adjustments to plans, and potential challenges with managing symptoms during social situations, which can leave loved ones feeling frustrated or unsure how to best offer support.

For example, the survey found that people with IBD missed out on a variety of events and moments because of their IBD in the past 12 months, possibly making them feel disconnected from loved ones. On average, these can range from missing everyday activities like work (14 days), religious services (6 services), and social events, to major life events like weddings, funerals, and birthday parties (4 events), and travel or vacation plans (4 vacation plans).

The survey also found that in the past 12 months, people who are Hispanic (77%) and Black (77%) are more likely to miss travel/vacation plans compared to people who are White (66%).§

A cross-sectional study of adults with IBD examining the impact of the disease on home life and close relationships also found that about half of respondents reported difficulties with domestic activities (55%) and parenting (51%), and one-third or more felt that IBD influenced their interpersonal relationships (39%) or desire to have children (33%).39

Romantic relationships and dating

Dating and relationships can also be more challenging with IBD, with many people reporting feelings of anxiety and embarrassment around disclosing their IBD to new connections. Although most people with the disease can be sexually intimate, the disease course, medication, surgery, and symptoms—like abdominal pain, diarrhea, incontinence, and urgency—along with fears of pregnancy (eg, complications during pregnancy, passing the disease on to their child40), can sometimes pose obstacles, including hindering one’s sex drive (libido).41 The rate of sexual dysfunction, the inability to experience satisfying sexual activity, in IBD patients ranges from 40%-66% in females and 44%-54% in males.42 One study also revealed that approximately 40% of people with IBD say their disease has prevented them from pursuing intimate relationships.43

Surgical procedures, such as ileoanal pouch formation, or the presence of fistulae in the perianal region or genitalia can also leave individuals without clear guidance around potential limitations on their sexual activity. At times, people with IBD may have to make significant changes to their preferred sexual activities.

Body image issues stemming from IBD, such as weight loss, hair loss, steroid-related weight gain, ostomy

Surgical procedures, such as ileoanal pouch formation, or the presence of fistulae in the perianal region or genitalia can also leave individuals without clear guidance around potential limitations on their sexual activity. At times, people with IBD may have to make significant changes to their preferred sexual activities.

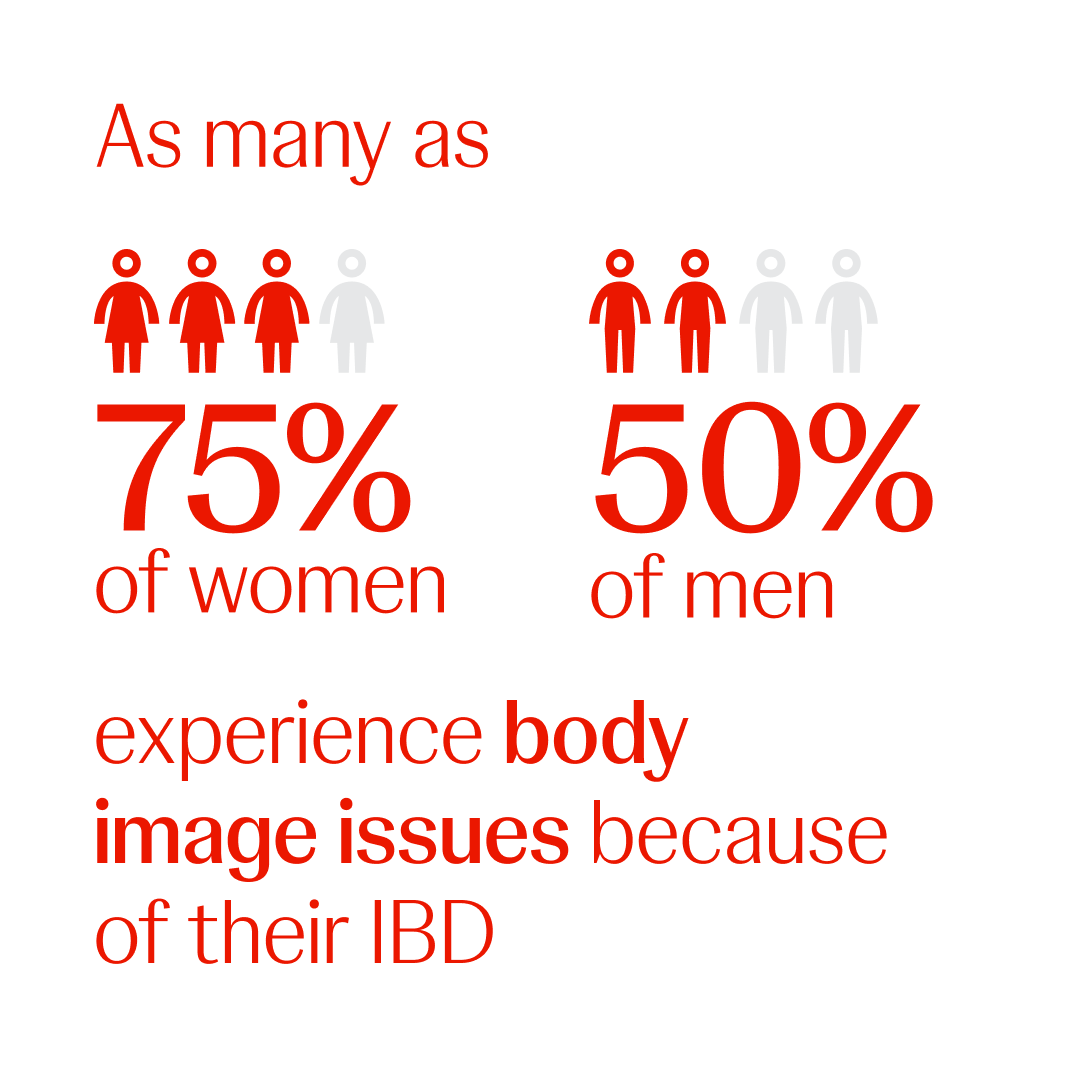

Body image issues stemming from IBD, such as weight loss, hair loss, steroid-related weight gain, ostomy bags, fistulae, skin manifestations of the disease, and more, can also affect dating and relationships. As many as 75% of women and 50% of men experience body image issues because of their IBD.44

Surgical procedures, such as ileoanal pouch formation, or the presence of fistulae in the perianal region or genitalia can also leave individuals without clear guidance around potential limitations on their sexual activity. At

Surgical procedures, such as ileoanal pouch formation, or the presence of fistulae in the perianal region or genitalia can also leave individuals without clear guidance around potential limitations on their sexual activity. At times, people

times, people with IBD may have to make significant changes to their preferred sexual activities.

with IBD may have to make significant changes to their preferred sexual activities.

Body image issues stemming from IBD, such as weight loss, hair loss, steroid-related weight gain, ostomy bags, fistulae, skin manifestations of the disease, and more, can also affect dating and relationships. As many as 75% of women and 50% of men experience body image issues because of their IBD.44

bags, fistulae, skin manifestations of the disease, and more, can also affect dating and relationships. As many as 75% of women and 50% of men experience body image issues because of their IBD.44

People with IBD who identify as LGBTQ+ may also face additional challenges with intimacy and relationships. For many, sharing their IBD diagnosis can feel as daunting as “coming out” about their sexuality.45

Race, ethnicity, culture, and socioeconomics

IBD has historically affected White populations at a higher prevalence than other groups; however, the incidence of IBD is increasing in all races and ethnicities across the US, including in people who are Black, Hispanic, Latino, and East or Southeast Asian.46-48

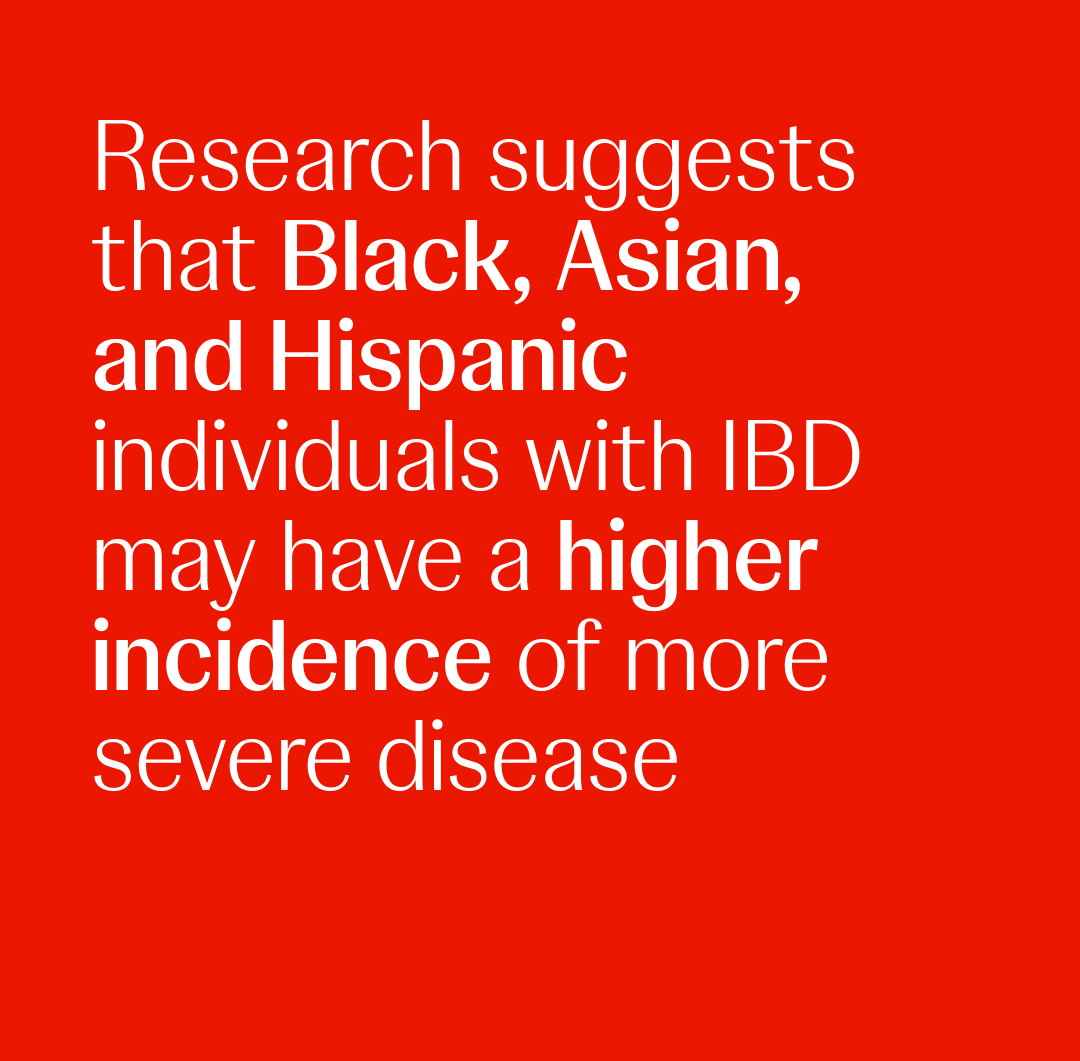

Research also suggests that Black, Asian, and Hispanic individuals with IBD may have a higher incidence of more severe disease.48

IBD has historically affected White populations at a higher prevalence than other groups; however, the incidence of IBD is increasing in all races and ethnicities across the US, including in people who are Black, Hispanic, Latino, and East or Southeast Asian.46-48

IBD has historically affected White populations at a higher prevalence than other groups; however, the incidence of IBD is increasing in all races and ethnicities across the US, including in people who are

Black, Hispanic, Latino, and East or Southeast Asian.46-48

Research also suggests that Black, Asian, and Hispanic individuals with IBD may have a higher incidence of more severe disease.48

People of color may struggle to receive a timely diagnosis and are less likely to receive the treatment and care they need under an IBD specialist/gastroenterologist compared to White people. Typically, people of color experience poorer outcomes compared to White individuals, with racial and ethnic disparities in IBD care and outcomes rooted in longstanding injustice and inequities in the social drivers of health.49 For example, one study found that Black children were more likely to get diagnosed a full 12 years after the presentation of symptoms, raising concerns that long delays in diagnosis were due to a low index of suspicion for IBD in children of color.50

People of color also experience more social barriers, such as financial strains and poor health literacy, with the greatest number of social barriers reported by non-Hispanic Black people, followed by Hispanic individuals.51 The stigma around IBD has also been shown to affect care for people of color, with language barriers and gaps in referrals to specialists impacting access to optimal care.52

Social drivers of health also impact the quality of care that people with IBD may receive. For example, Black individuals and those who live in rural areas or urban, low socioeconomic communities are less likely to be under the care of an IBD specialist or gastroenterologist.52 Furthermore, when people of color see specialists, they may feel it’s important to receive culturally conscious care that incorporates their culture, family, dietary preferences, and individual preferences into treatment and disease management decisions.53

Diet considerations

While there are many contributing factors to diet and choice, diets recommended in patients with IBD may not consider one’s cultural diet and needs. Notably, foods and beverages that are staples among certain populations may be on the list of foods people with IBD should avoid (eg, fried or greasy foods, spicy foods, sugar-sweetened drinks, whole-fat dairy).52 Also, it is not just the “unhealthy” or “junk” foods that can exacerbate symptoms, particularly when experiencing a flare-up. Symptoms during flare-ups (such as abdominal pain and diarrhea) may worsen in some people who consume certain foods, such as those high in fiber, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, or dairy products.54 However, food and beverage types may aggravate symptoms in IBD differently in each person.

Another challenge is that many HCPs will instruct their patients with IBD to follow a specific diet, such as the Mediterranean Diet, to help manage their symptoms and improve the gut microbiome.55 However, they may not recognize that these diets are not always compatible with cultural preferences or food access, and that this can exacerbate feelings of shame and social isolation. In fact, research suggests that up to three-quarters of people with IBD have expressed decreased satisfaction in eating since their diagnosis, sometimes due to the above challenges.56

Healthcare journey and treatment decisions

HCPs play a critical role in the community sphere for people with IBD. However, ongoing obstacles and structural barriers prevent some people with IBD from building trust with their healthcare team, which may, in turn, negatively impact health outcomes. People with IBD often cite that securing patient-centered, “whole self” care is challenging and that failing to receive this type of care from physicians can hinder trust.57

“Whole self” treatment includes looking beyond the physical symptoms of the disease and addressing the psychological and social impacts through mental health support, nutrition and diet counseling, coordination with other specialists to address comorbidities, and more.58 Under this model, members of a healthcare team can include gastroenterologists, advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, registered nurses, psychologists, registered dietitians, pharmacists, primary care physicians, dermatologists, rheumatologists, endocrinologists, and gynecologists, among others.

In fact, research indicates that people with IBD who are treated by an integrated team of providers and specialists may achieve improved health outcomes, as one study revealed they tend to undergo IBD-related surgeries less often and are more likely to receive advanced therapies for treatment management.59

Patients living with IBD are more than a GI tract. They are a whole person with a disease that negatively impacts many aspects of their life, and many patients feel that others (including friends and family) do not fully understand how IBD is affecting their psychosocial health, relationships, work, finances, and simple daily activities.

As their healthcare team, we have a unique opportunity to establish a working connection based on trust and empathy by acknowledging the struggles they face as a person, and become part of their support system. In other words, they know we’ve got their back and not just their GI tract! Once you establish this type of connection, patients become true partners in their care, more confident that their quality of life will improve with the right support, more empowered to advocate for themselves, and, overall, have a more positive outlook on their future living with IBD.”

For most people living with IBD, the majority of community support comes from care partners, children, spouses, parents, extended family, friends, and their healthcare team. However, the extent of support can look different for everyone, with some people forced to manage their disease more independently.

History of IBD

For many years, little was known about IBD. For example, reports of individuals with UC symptoms date back to before the US Civil War, but UC was not named a distinct disease until 1875.60 In the decades following, people living with IBD often handled it privately with their families, struggling to manage a disease that was poorly understood by the healthcare community, let alone the broader public.

In 1967, the first advocacy and support organization for people with IBD was formed by families that recognized the need for better education, support, and resources. This advocacy led to in-person events and groups that offered people with IBD and their loved ones a forum to connect with others, learn from each other, and show support.60

The emergence of online communities

The internet plays an increasingly important role in our everyday lives, and has rapidly become an easily accessible, user-friendly source of health-related information, advice, and support.61 As the internet evolved, online communities such as chat rooms emerged as places for people to share their experiences and connect with others. Patient support in healthcare experienced a major transformation with the launch of Facebook, which quickly gained popularity due to ease of access. The platform gave people with conditions like IBD access to online peer-to-peer support communities.61

Today, through online support communities, individuals can interact with others like them through either synchronous (eg, chat rooms) or asynchronous (eg, discussion forums) communication; these communities may be professionally moderated or peer moderated.

The rise in popularity of online support communities can be explained by several differentiating factors of online communication:

- Access to 24/7 support makes it more convenient than in-person engagements, while reducing difficulties that might be associated with traveling to, or accessing, traditional face-to-face support groups.

- The anonymous nature of the internet makes it easier for individuals to discuss sensitive or embarrassing topics, and may increase honesty, intimacy, and self-disclosure.61

- Online support communities do not limit the number of people who can join them, thereby allowing members access to a potentially broader range of experiences and opinions than would be available in the face-to-face setting.

Characterizing online communities and digital resources in IBD care

People with IBD trust their healthcare team and loved ones for guidance and support with their disease, yet they still crave additional information and resources from peers within the IBD community. According to the survey, while a majority of people with IBD feel comfortable talking with their HCPs (91%), they are also comfortable speaking with care partners (among those who have one; 88%), other IBD community members (including patients or support groups; 85%), and their spouse/partner (81%) about their IBD.

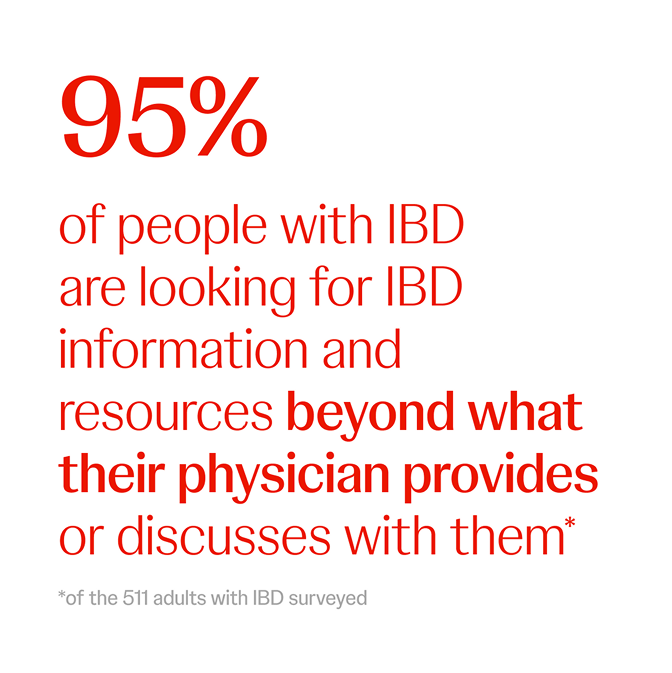

Furthermore, nearly all people with IBD (95%) are looking for IBD information and resources beyond what their physician provides or discusses with them. These individuals want (greater) access to IBD resources, with nearly seven in 10 (69%) looking for online (47%) and in-person (39%) IBD support groups.

Patient advocates and online support communities can play an important role in providing support, such as helping educate people impacted by IBD and combating misinformation.62 The internet and social media may promote misinformation, anxiety, fear, and stress related to IBD,62,63 putting the onus on the individual to seek out credible sources of information when they already may feel overwhelmed. Many find online IBD communities to be more credible, as they can hear and learn directly from others who have lived experiences. According to the survey, some of the key reasons people with IBD look for additional resources and support, beyond what their HCP has shared or discussed with them, include wanting to learn and hear from other people who are living with IBD (32%), needing more “real world” tips and advice (29%), and needing more information relevant to their cultural background (19%).

Patient engagement with IBD online communities occurs in a wide range of forums. The survey found that 42% of people with IBD have participated in online IBD support groups, 37% have engaged with social media forums or group chats on platforms like Facebook and Reddit, and 28% have followed influencers who share their IBD journey on social media platforms.

Patient engagement with IBD online communities occurs in a wide range of forums. The survey found that 42% of people with IBD have participated in online IBD support groups, 37% have engaged with social media forums or group chats on platforms like Facebook

Patient engagement with IBD online communities occurs in a wide range of forums. The survey found that 42% of people with IBD have participated in online IBD support groups, 37% have engaged with social media forums or

group chats on platforms like Facebook and Reddit, and 28% have followed influencers who share their IBD journey on social media platforms.

and Reddit, and 28% have followed influencers who share their IBD journey on social media platforms.

A range of digital resources have also emerged from advocacy groups and industry leaders to increase access to tools that help educate people with IBD on how to navigate life with the disease and find ways to help improve patient outcomes. These include mobile apps, online self-management tools and resources, telemedicine platforms, telemonitoring, wearable devices, home tests, patient-to-patient connections, and big data consolidation to complement treatment practices. These digital resources have shown to be helpful for disease management through consistent monitoring of symptoms and treatment response, increased accessibility of care, and enhanced patient education, which can help lead to improved health outcomes and reduced healthcare utilization.64,65

Many resources have emerged to focus on specific challenges with the disease, such as parenting, relationships, and more. In addition, to address disparities experienced by minority groups, digital resources have also been developed to address language barriers, link patients to HCPs who share their cultural background to promote physician-patient trust, and provide culturally appropriate information and guidance, including dietary recommendations.53

According to the survey, people with IBD who have ever engaged with the IBD community—86% of all IBD patients surveyed—report a wide range of impacts on their lives and ways that engaging with the IBD community has helped them to better manage their IBD.

Through IBD community engagement and support, patients have reported positive impacts‖ on:

Physical well-being and treatment decisions

- 39% reported that it has helped them identify ways to make improvements in their physical health and well-being

- 39% learned how to improve their ability to communicate with their HCPs

- 39% became more informed about IBD treatment options, including different treatment options they did not know about before

- 32% learned how to better advocate for themselves with their HCPs

Mental health and feelings of loneliness and isolation

- 44% reported feeling improvements in their mental health and well-being

- 38% noted it contributed to improvements in quality of life

- 36% felt their feelings about living with IBD were validated

- 34% felt more optimistic about the future

- 33% felt less isolated

Access to disease management strategies and resources validated by other people

- 41% learned about strategies and techniques to help manage IBD

- 33% cited access to more, easier to understand educational resources to learn about IBD

- 30% noted the ability to ask tough questions that they would not otherwise ask

- 24% of those who have a care partner reported reduced burden on their care partner(s)

Emerging research even suggests that community support may help improve health outcomes. One study found that social support was positively associated with health-related quality of life for people with IBD.66

While there are many benefits to engaging with the IBD community online, there remains a need to address several obstacles to increased participation. These obstacles include hesitancy to join, technological barriers, privacy concerns, language barriers, and embarrassment to share one’s journey.

In the survey, more than two-thirds (68%) agreed that they would like to join an online IBD support group but do not have access to the adequate technology (eg, the right device, stable internet connection, etc). Hispanic people with IBD are more likely than their White counterparts to say they would like to join an online IBD support group but they, too, do not have access to the adequate technology (82% vs. 61%). Increasingly, access to the internet is being viewed as a social driver of health. More than 42 million people in the US still do not have access, with people of color, lower-income individuals, and those who live in rural areas most heavily impacted.67

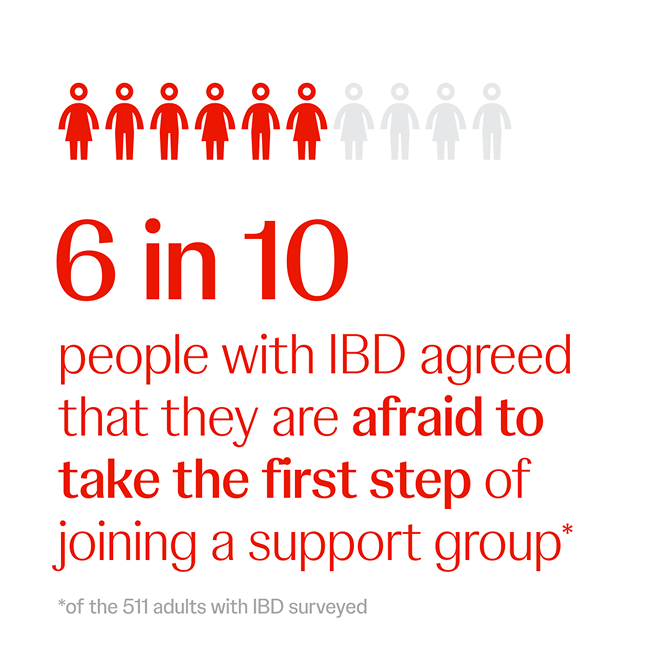

According to the survey, six in 10 people with IBD (60%) agreed that they are afraid to take the first step of joining a support group. Among the one in seven (14%) who have not engaged with the IBD community, concerns over privacy (34%) and difficulty or embarrassment over talking about IBD (31%) are the most common barriers cited. §

According to the survey, six in 10 people with IBD (60%) agreed that they are afraid to take the first step of joining a support group. Among the one in seven (14%) who have not engaged with the IBD community, concerns over

privacy (34%) and difficulty or embarrassment over talking about IBD (31%) are the most common barriers cited. §

Challenges in accessing support among people of color

While little research has been done in IBD specifically, studies show that people of color are generally less likely to seek out social support, mental health resources, and communities due to cultural stigma. For example, Black men are less likely to seek mental health services because they are often socialized to handle difficulties or problems by not demonstrating stress or suppressing the intensity of stressors; they may also avoid seeking mental health services due to the stigma associated with formal services and a belief that they will experience discrimination.68,69

A study examining the use of online mental health services by Hispanic populations in the US found that participants cited not wanting others to know that they needed treatment, worrying about the effects on their jobs, and not having enough time as some of the top barriers. Spanish-speaking Latinos in the study were also less likely to access these online services, in part due to language and literacy challenges.70

Another important consideration is that people with IBD may not feel as empowered to participate in online communities and support groups based on where they are in their disease journey. Despite these groups existing to bring people with similar—or even dissimilar—experiences together, those who achieve remission, for example, may begin to feel misplaced in online communities and feel they cannot contribute to discussions given that they now have their symptoms under control. However, they still need and deserve continued support from the IBD community.

The burden of IBD goes well beyond physical manifestations impacting mental health and quality of life. People living with the disease are at a higher risk for depression and anxiety than the average population, and the physical symptoms leave many sufferers embarrassed and stigmatized, creating a feeling of isolation from family, friends, and coworkers.

Despite the challenges faced by people living with the disease, people with IBD overwhelmingly seek out IBD information, resources, and a sense of community and support that extends well beyond what they can get from their HCPs. In fact, people who have engaged others in the IBD community feel that doing so has changed the trajectory of their IBD journey for the better, has helped improve their quality of life, and helped them better advocate for their care.

Despite the challenges faced by people living with the disease, people with IBD overwhelmingly seek out IBD information, resources, and a sense of community and support that extends well beyond what they can get from their HCPs. In fact, people who have engaged

Despite the challenges faced by people living with the disease, people with IBD overwhelmingly seek out IBD information, resources, and a sense of community and support that extends well beyond what they can get from

their HCPs. In fact, people who have engaged others in the IBD community feel that doing so has changed the trajectory of their IBD journey for the better, has helped improve their quality of life, and helped them better advocate for their care.

others in the IBD community feel that doing so has changed the trajectory of their IBD journey for the better, has helped improve their quality of life, and helped them better advocate for their care.

Looking ahead, there are steps that all stakeholders in the IBD community can take to help improve community support and limit isolation for people living with this disease.

Healthcare team

Social isolation and loneliness in this patient population are pervasive. Remember to ask all patients how they are feeling, regardless of the severity of their symptoms or whether or not they are in clinical remission, and have information on culturally conscious resources and community support groups on hand to share with those who are in need.

Treating the whole patient is also critical to ensure all aspects of the disease are being treated. When possible, work collaboratively with other providers and specialists, including gastroenterologists, advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, registered nurses, psychologists, registered dietitians, pharmacists, primary care physicians, dermatologists, rheumatologists, endocrinologists, and gynecologists, as appropriate. Also, be open to shared decision-making with your patients.

Finally, remember that finding community as a care team is critically important—learn from other providers who are also treating IBD on the front lines and feel empowered to share care strategies and stories with others.

People living with IBD

Be an advocate for yourself and, by extension, the IBD community. Engaging with online communities to hear and share lived experiences can, quite literally, save a life. Be courageous to share your journey with members of your community who you trust.

To find a community that is right for you, talk to your HCP to help identify resources. Also, engage others with IBD on social media or reach out to IBD advocacy groups for guidance on what communities are available.

Care partners

A care partner plays a critical role in offering support, including tangible support (delivering a meal, accompanying the patient to procedures), emotional support (listening, words of affirmation), and informational support (sharing opportunities to join a community, researching the latest in IBD care). A care partner can be an advocate for their loved one while also respecting their loved one by not giving unsolicited advice and trusting their medical team to help make informed decisions. However, this can take its toll on the care partner, and connecting with other care partners to get support and share learnings is critical to prevent burnout.

Family and friends

When supporting someone with IBD, remember that their needs will ebb and flow and the extent to which they can be present and available will evolve as their disease evolves. Recognize that it should not be considered personal when plans change due to a flare-up or another disease-related need. But continuing to encourage them to be social and going the extra mile to support them can help tremendously. Ask how you can support them and check in with them regularly, as their needs may change over time.

Broader public

The extensive impact of IBD is largely misunderstood and underestimated by the broader public, making those living with the disease feel further isolated and stigmatized. As a society, we must learn to be more empathetic to those living with invisible illnesses like IBD, where the impact and severity may not be immediately apparent.

Broad awareness can also be driven from within the IBD community. By sharing lived experiences and being open with neighbors, acquaintances, and friends, we can begin to normalize the IBD experience at the societal level.

Johnson & Johnson is committed to empowering people living with IBD, care partners, and others to prompt more informed conversations with community members and their HCPs. Through its support of IBD Social Circle over the last decade, Johnson & Johnson has been working with the IBD community, elevating the voices of the people directly impacted by IBD, care partners, and HCPs to forge supportive connections and help remove the isolation and stigma so many of these people feel.

For more information, resources, and ways to connect with their community, or to find one, visit www.ibdsocialcircle.com.

cp-517436v1

Footnotes

* All references to the survey are related to the Johnson & Johnson survey.

† Median

‡ 82% of those age 18-34 and 81% of those 35-44 say their school or work is negatively impacted by their IBD, versus 72% of those 45 or older.

§ Results based on small subset of total sample (n<100).

‖ These results are based on self-reported data and should be viewed as personal experiences only.

Appendix

Full Harris Poll methodology statement

Method, audience, and field timing

The research was conducted online in the US by The Harris Poll on behalf of Johnson & Johnson among 511 US adults aged 18 and over who have ever been diagnosed with, and are currently living with or managing, IBD—including IBD, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis; if the respondent was living with or managing both IBD and IBS, their current diagnosis was classified as IBD. The survey was conducted June 26, 2024 to July 9, 2024.

Recruitment, weighting, and representativeness

Respondents for this survey were selected from among those who have agreed to participate in our surveys. Raw data were not weighted and are therefore only representative of the individuals who completed the survey.

The sampling precision of The Harris Poll online polls is measured by using a Bayesian credible interval. For this study, the sample data is accurate to within ± 4.3 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. This credible interval will be wider among subsets of the surveyed population of interest.

Limitations

All sample surveys and polls, whether or not they use probability sampling, are subject to other multiple sources of error, which are most often not possible to quantify or estimate, including, but not limited to, coverage error, error associated with nonresponse, error associated with question wording and response options, and post-survey weighting and adjustments.

Other limitations include (but are not limited to):

- Bias associated with panel membership and internet access

- Reliance on self-report of diagnosis with IBD/qualifying conditions

- Recall error

References

- Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003

- Burisch J, Hart A, Sturm A, et al. Residual disease burden among European patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A real-world survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2025;31(2):411-424. doi:10.1093/ibd/izae119

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. What is Crohn’s disease? Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/patientsandcaregivers/what-is-crohns-disease

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. What is ulcerative colitis? Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ulcerative-colitis

- Taft TH, Keefer L. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:49-58. doi:10.2147/CEG.S83533

- Vernon-Roberts A, Gearry RB, Day AS. The level of public knowledge about inflammatory bbowel disease in Christchurch, New Zealand. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2020;5(4):205-211. doi:10.1159/000510071

- Blackwell J, Saxena S, Jayasooriya N, et al. Prevalence and duration of gastrointestinal symptoms before diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease and predictors of timely specialist review: A population-based study. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(2):203-211. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa146

- Taft TH, Ballou S, Bedell A, Lincenberg D. Psychological considerations and interventions in inflammatory bowel disease patient care. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):847-858. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2017.08.007

- Chew D, Zhiqin W, Ibrahim N, Ali RAR. Optimizing the multidimensional aspects of the patient-physician relationship in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res. 2018;16(4):509-521. doi:10.5217/ir.2018.00074

- Boyce L, Harun A, Prybutok G, Prybutok VR. The role of technology in online health communities: A study of information-seeking behavior. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(3):336. doi:10.3390/healthcare12030336

- GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17-30. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30333-4

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IBD facts and stats. 2024. Accessed April 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/inflammatory-bowel-disease/php/facts-stats/index.html

- Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2011;7(4):235-241.

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Extraintestinal complications of IBD. Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ibd/extraintestinal-complications-ibd

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What causes IBD? Accessed April 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/inflammatory-bowel-disease/causes/index.html

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). 2024. Accessed April 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/inflammatory-bowel-disease

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. How is IBD diagnosed? Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/patientsandcaregivers/what-is-ibd/diagnosing-ibd

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756-1770.

- Sajadinejad MS, Asgari K, Molavi H, et al. Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:106502. doi:10.1155/2012/106502

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Partnering with your doctor. Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/patientsandcaregivers/effective-partnering

- Chang S, Malter L, Hudesman D. Disease monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(40):11246-11259. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i40.11246

- Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Defining and predicting deep remission in patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease on anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(34):6197-6200. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6197

- Nardone OM, Calabrese G, La Mantia A, Caso R, Testa A, Castiglione F. Insights into disability and psycho-social care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1416054. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1416054

- Youseff M, Hossein-Javaheri N, Hoxha T, Mallouk C, Tandon P. Work productivity impairment in persons with inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2024;18(9):1486-1504. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjae057

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Crohn's & Colitis Foundation survey reveals more than 40% of IBD patients made significant financial sacrifices to pay for their healthcare. Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/crohns-colitis-foundation-survey-reveals-more-40-of-ibd-patients-made-significant-financial

- The University of Chicago Medicine. Searching for links between IBD and mental health, through the gut microbiome. Accessed April 2025. https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/gastrointestinal-articles/searching-for-links-between-ibd-and-mental-health-through-the-gut-microbiome

- Stroie T, Preda C, Istratescu D, Ciora C, Croitoru A, Diculescu M. Anxiety and depression in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease: The role of fatigue and health-related quality of life. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(19):e33713. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000033713

- Crohn’s disease and anxiety: What’s the link? Healthline. Published January 18, 2024. Accessed April 2025. https://www.healthline.com/health/crohns-disease/link-between-crohns-disease-and-anxiety

- Taft TH, Quinton S, Jedel S, Simons M, Mutlu EA, Hanauer SB. Posttraumatic stress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and relationships to patient-reported outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(5):710-719. doi:10.1093/ibd/izab152

- Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, Horne R. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):525-39. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.685

- Lenti MV, Cococcia S, Ghorayeb J, Di Sabatino A, Selinger CP. Stigmatisation and resilience in inflammatory bowel disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(2):211-223. doi:10.1007/s11739-019-02268-0

- Taft TH, Keefer L. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:49-58. doi:10.2147/CEG.S83533

- Degnan A, Berry K, Humphrey C, Bucci S. The relationship between stigma and subjective quality of life in psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102003

- Ammirati RJ, Lamis DA, Campos PE, Farber EW. Optimism, well-being, and perceived stigma in individuals living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2015;27(7)926-933 doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1018863

- Shi Y, Wang S, Ying J et al. Correlates of perceived stigma for people living with epilepsy: A meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;70 (Pt A):198-203. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.02.022

- Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, Nealon-Woods M. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflammation Bowel Dis. 2009;14(8):1224-132. doi:10.1002/ibd.20864

- Gamwell KL, Baudino MN, Bakula DM et al. Perceived illness stigma, thwarted belongingness, and depressive symptoms in youth with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Inflammation Bowel Dis. 2018;24(5):960-965. doi:10.1093/ibd/izy011

- Guo L, Rohde J, Farraye FA. Stigma and disclosure in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammation Bowel Dis. 2020;26(7):1010-1016. doi:10.1093/ibd/izz260

- Paulides E, Cornelissen D, de Vries AC, van der Woude CJ. Inflammatory bowel disease negatively impacts household and family life. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;13(5):402-408. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2021-102027

- Ellul P, Zammita SC, Katsanos KH, et al. Perception of reproductive health in women with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(8):886-91. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw011

- Fourie S, Norton C, Jackson D, Czuber-Dochan W. Grieving multiple losses: Experiences of intimacy and sexuality of people living with inflammatory bowel disease. A phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 2024;80(3):1030-1042. doi:10.1111/jan.15879

- Zhang J, Wei S, Zeng Q, Wu X, Gan H. Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. [published correction appears in Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Sep;36(9):2039. doi: 10.1007/s00384-021-03987-7.]. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(9):2027-2038. doi:10.1007/s00384-021-03958-y

- Leenhardt R, Rivière P, Papazian P, et al. Sexual health and fertility for individuals with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(36):5423-5433. doi:10.3748/wjg.v25.i36.5423

- Jedel S, Hood M MM, Keshavarzian A. Getting personal: A review of sexual functioning, body image, and their impact on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [Review]. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(4):923-938. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000257

- Global Health Living Foundation. Ensuring equity in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) care for LGBTQ+ people. 2023. Accessed April 2025. https://ghlf.org/inflammatory-bowel-disease/ibd-lgbtq-health-disparities/

- Nguyen GC, Chong CA, Chong RY. National estimates of the burden of inflammatory bowel disease among racial and ethnic groups in the United States. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(4):288-295.

- WebMD. Are there racial disparities in ulcerative colitis? 2024. Accessed April 2025. https://www.webmd.com/ibd-crohns-disease/ulcerative-colitis/racial-disparities-uc

- Shah S, Shillington AC, Kabagambe EK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: An online survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024;30(9):1467-1474. doi:10.1093/ibd/izad194

- Odufalu FD, Aboubakr A, Anyane-Yeboa A. Inflammatory bowel disease in underserved populations: lessons for practice. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38(4):321-327. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000855

- Liu JJ, Abraham BP, Adamson P, et al. The current state of care for black and hispanic inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(2):297-307. doi:10.1093/ibd/izac124

- Damas OM, Kuftinec G, Khakoo NS, et al. Social barriers influence inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) outcomes and disproportionally affect Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks with IBD. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221079162. doi:10.1177/17562848221079162

- Roland J, Nazario B. A change of thought: Shifting perception of Crohn’s among minorities. WebMD. 2023. Accessed April 2025. https://www.webmd.com/ibd-crohns-disease/crohns-disease/crohns-perceptions-minorities

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60-e76. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Managing flares and IBD symptoms. 2019. Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/managing-flares-brochure-final-online.pdf

- Ratajczak AE, Festa S, Aratari A, Papi C, Dobrowolska A, Krela-Kaźmierczak I. Should the Mediterranean diet be recommended for inflammatory bowel diseases patients? A narrative review. Front Nutr. 2023;9:1088693. Published 2023 Jan 10. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1088693

- Godala M, Gaszyńska E, Durko Ł, Małecka-Wojciesko E. Dietary behaviors and beliefs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Med. 2023;12(10):3455. doi:10.3390/jcm12103455. PMID: 37240560; PMCID: PMC10219397.

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. Treatment approaches: Shared decision-making. Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/patientsandcaregivers/shared-decision-making

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Whole person health: What it is and why it's important. Accessed April 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/whole-person-health-what-it-is-and-why-its-important

- American Journal of Managed Care. Integrated care model linked to better IBD management in population-based study. Accessed April 2025. https://www.ajmc.com/view/integrated-care-model-linked-to-better-ibd-management-in-population-based-study

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. A look back at our beginning. Accessed April 2025. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/about/our-beginning

- Coulson NS. How do online patient support communities affect the experience of inflammatory bowel disease? An online survey. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4(8):2042533313478004. doi:10.1177/2042533313478004

- Cury DB, Paez LEF, Micheletti AC, et al. The impact of electronic media on patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:809-813. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S285088

- Groshek J, Basil M, Guo L, et al. Media consumption and creation in attitudes toward and knowledge of inflammatory bowel disease: Web-based survey. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(12):e403. doi:10.2196/jmir.7624

- Zhen J, Marshall JK, Nguyen GC, et al. Impact of digital health monitoring in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. J Med Syst. 2021;45(2):23. doi:10.1007/s10916-021-01706

- Hoyo JD, Millán M, Garrido-Marín A, Aguas M. Are we ready for telemonitoring inflammatory bowel disease? A review of advances, enablers, and barriers. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29(7):1139-1156. doi:10.3748/wjg.v29.i7.1139

- Fu H, Kaminga AC, Peng Y, et al. Associations between disease activity, social support and health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: the mediating role of psychological symptoms. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020:20(1):11. doi:10.1186/s12876-020-1166-y

- Harvard Public Health. Digital redlining perpetuates health inequity. Here’s how we fix it. Accessed April 2025. https://harvardpublichealth.org/equity/bridging-the-digital-divide-is-a-prescription-for-health-equity/

- DeAngelis T. Helping Black men and boys gain optimal mental health. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/09/ce-black-mental-health

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. Black Men and Mental Health: Practical Solutions. Accessed April 2025. https://www.nami.org/african-american/black-men-and-mental-health-practical-solutions/

- Parra-Cardona JR, DeAndrea DC. Latinos’ access to online and formal mental health support. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43(2):281-292. doi:10.1007/s11414-014-9420-0

Social stigma

Social stigma—including feelings of being judged for the frequency of bathroom visits and the need to hide their symptoms—is another psychosocial burden that people with IBD may experience.31,32 People with chronic diseases, such as psychiatric disorders,33 HIV,34 and epilepsy,35 have also been shown to be impacted by stigmas. One study reported that perceived stigma may be experienced by up to 84% of people with IBD.36 Stigmas may be associated with a higher prevalence of depression, social withdrawal, and poorer quality of life.37,38

Overall, these individuals may feel embarrassed by frequent trips to the bathroom or worry about how food and activity might trigger flare-ups. They may also be embarrassed by bowel incontinence that makes them feel unattractive or unhygienic, colostomy bags that can be problematic for physical intimacy, or bathroom trips that make it difficult to attend exercise classes or group outings, as well as feeling self-conscious after ostomy surgery.31

Tina Aswani-Omprakash, MPH

IBD Social Circle advocate

In the survey, 78% of those surveyed reported that they felt isolated as a result of their IBD, and additional studies further highlight that it can be an isolating experience to carry the physical and emotional burdens due to the disease.5,19 But, as this is often an “invisible disease,” the people they encounter may not always be able to see or empathize with what they are going through.